How Many Immigrants Came to the Us in 2017

Migration flows: Immigration to the EU from non-member countries was 2.7 million in 2019

A total of 4.2 million people immigrated to one of the EU Member States during 2019, while 2.7 million emigrants were reported to have left an EU Member State. However, these total figures do not represent the migration flows to/from the EU as a whole, since they also include flows between different EU Member States. In 2019, there were an estimated 2.7 million immigrants to the EU from non-EU countries and about 1.2 million people emigrated from EU to a country outside the EU - see Figure 1. In addition, 1.4 million people previously residing in one EU Member State migrated to another Member State.

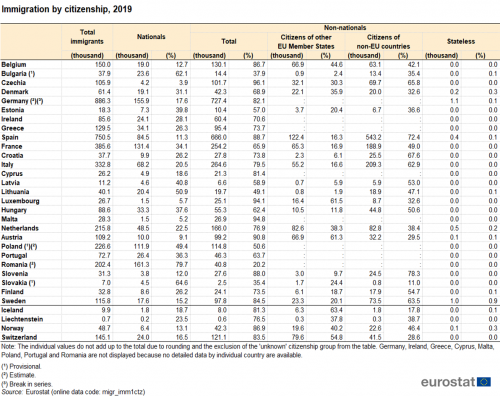

Germany: the largest number of immigrants and emigrants

Germany reported the largest total number of immigrants (886.3 thousand) in 2019, followed by Spain (750.5 thousand), France (385.6 thousand) and Italy (332.8 thousand). Germany also reported the highest number of emigrants in 2019 (576.3 thousand), followed by France (299.1 thousand), Spain (296.2 thousand) and Romania (233.7 thousand). A total of 22 of the EU Member States reported more immigration than emigration in 2019, but in Bulgaria, Croatia, Latvia, Denmark and Romania the number of emigrants outnumbered the number of immigrants.

Table 1: Immigration by citizenship, 2019

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm1ctz)

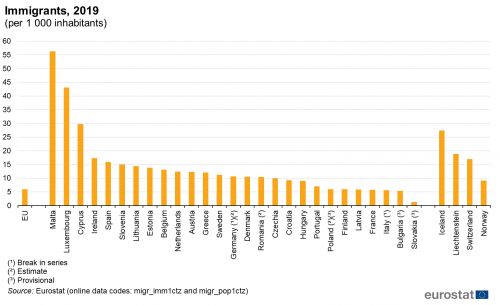

Relative to the size of the resident population, Malta recorded the highest rates of immigration in 2019 (56 immigrants per 1 000 persons), followed by Luxembourg (43 immigrants per 1 000 persons) — see Figure 2. For emigration, the highest rates in 2019 were reported for Luxembourg (25 emigrants per 1 000 persons), Cyprus (20 emigrants per 1 000 persons) and Malta (16 emigrants per 1 000 persons).

Highest share of national immigrants for Romania, lowest for Czechia

In 2019, the relative share of national immigrants (immigrants with the citizenship of the EU Member State to which they were migrating) within the total number of immigrants was highest in Romania (80 % of all immigrants), Slovakia (65 %), Bulgaria (62 %), Lithuania (51 %) and Poland (49 %). These were the only EU Member States where national immigration accounted for more than half of the total number of immigrants — see Figure 3. By contrast, in Czechia, national immigration represented less than 4 % of their total immigration in 2019.

Figure 3: Distribution of immigrants by citizenship, 2019

(% of all immigrants)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm2ctz)

Information on citizenship has often been used to study immigrants with a foreign background. However, since citizenship can change over the life-time of a person, it is also useful to analyse information by country of birth. The relative share of native-born immigrants within the total number of immigrants was highest in Bulgaria (59 % of all immigrants), followed by Romania (49 %) and Lithuania (46 %). By contrast, Luxembourg and Spain reported relatively low shares of native-born immigrants, 5 % or less of all immigration in 2019.

Table 2: Immigration by country of birth, 2019

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm3ctb)

Previous residence: 2.7 million immigrants entered the EU in 2019

An analysis by previous residence reveals that Luxembourg reported the largest share of immigrants coming from another EU Member State (91 % of its total number of immigrants in 2019), followed by Austria (63 %) and Slovakia (60 %); relatively low shares were reported by Spain as well as Slovenia (both 16 %) — see Table 3.

Table 3: Immigration by previous country of residence, 2019

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm5prv)

Regarding the sex distribution of immigrants to the EU Member States in 2019, there were slightly more men than women (54 % compared with 46 %). The Member State reporting the highest share of male immigrants was Croatia (77 %); by contrast, the highest share of female immigrants was reported in Cyprus (53 %).

Figure 4: Immigrants by sex, 2019

(% of all immigrants)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm2ctz)

Half of immigrants were aged under 29

Immigrants into EU Member States in 2019 were, on average, much younger than the total population already resident in their country of destination. On 1 January 2020, the median age of the total population of the EU stood at 43.9 years, while it was 29.2 years for immigrants in 2019.

Figure 5: Age structure of immigrants by citizenship, EU, 2019

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_imm2ctz)

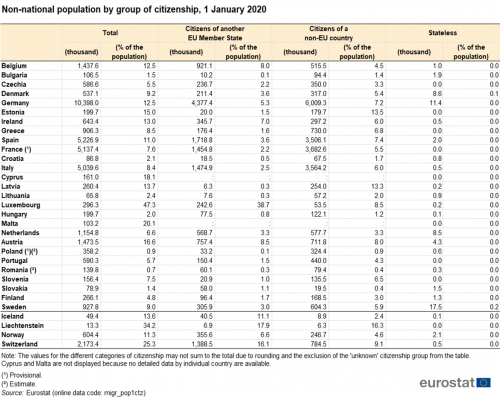

Migrant population: 23 million non-EU citizens living in the EU on 1 January 2020

The number of people residing in an EU Member State with citizenship of a non-member country on 1 January 2020 was 23 million, representing 5.1 % of the EU population. In addition, there were 13.5 million persons living in one of the EU Member States on 1 January 2020 with the citizenship of another EU Member State.

In absolute terms, the largest numbers of non-nationals living in the EU Member States on 1 January 2020 were found in Germany (10.4 million persons), Spain (5.2 million), France (5.1 million) and Italy (5.0 million).Non-nationals in these four Member States collectively represented 71 % of the total number of non-nationals living in all of the EU Member States, while the same four Member States had a 58 % share of the EU's population.

Table 4: Non-national population by group of citizenship, 1 January 2020

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

Foreign population made of non-EU citizens in most EU Member States

On 1 January 2020, Belgium, Ireland, Luxembourg, Austria and Slovakia were the EU Member States where non-nationals were mainly citizens of another EU Member State. This means that in most EU Member States, the majority of non-nationals were citizens of non-EU countries (see Table 5). In the case of Latvia and Estonia, the proportion of citizens from non-member countries is particularly large due to the high number of recognised non-citizens (mainly former Soviet Union citizens, who are permanently resident in these countries but have not acquired any other citizenship).

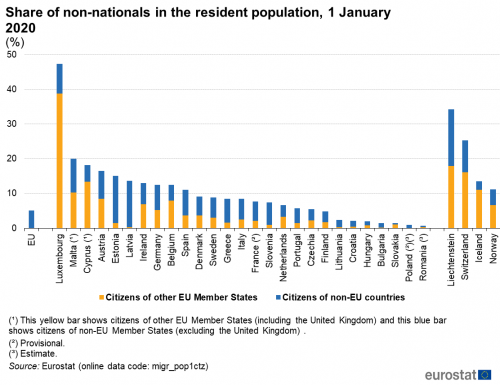

Figure 6: Share of non-nationals in the resident population, 1 January 2020

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

Highest share of foreign population in Luxembourg, lowest in Romania

In relative terms, the EU Member State with the highest share of non-nationals was Luxembourg, as non-nationals accounted for 47 % of its total population. A high proportion of foreign citizens (more than 10 % of the resident population) was also observed in Malta, Cyprus, Austria, Estonia, Latvia, Ireland, Germany, Belgium and Spain. In contrast, non-nationals represented less than 1 % of the population in Poland (0.9 %) and in Romania (0.7 %). The relative share of foreign-borns within the total population was highest in Luxembourg (48 % of the resident population), followed by Malta (23 %) and Cyprus (22 %). By contrast, Poland reported low shares of foreign-born, 2 % of its total population on 1 January 2020, followed by Bulgaria (2.7 %), Slovakia (3.6 %) and Romania (3.7 %).

Table 5: Foreign-born population by country of birth, 1 January 2020

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop3ctb)

Table 6 presents a summary of the five main groups of foreign citizens and foreign-born populations for the EU Member States and EFTA countries (subject to data availability).

Table 6: Main countries of citizenship and birth of the foreign/foreign-born population, 1 January 2020

(in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the total foreign/foreign-born population)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz) and (migr_pop3ctb)

Romanian, Polish, Italian and Portuguese citizens were the four biggest groups of EU citizens living in other EU Member States in 2020 (see Figure 7).

Figure 7: Number of EU citizens that are usual residents in the rest of the EU as of 1 January 2020

(million)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop1ctz)

Foreign citizens are younger than nationals

An analysis of the age structure of the population shows that, for the EU as a whole, the foreign population was younger than the national population. The distribution by age of foreigners shows, compared with nationals, a greater proportion of relatively young working age adults. On 1 January 2020, the median age of the national population in the EU was 45 years, while the median age of non-nationals living in the EU was 36 years.

Figure 8: Age structure of the national and non-national populations, EU, 1 January 2020

(%)

Source: Eurostat (migr_pop2ctz)

Acquisitions of citizenship: EU Member States granted citizenship to 706 thousand persons in 2019

Acquisitions of citizenship were up by 5 % in 2019

The number of people acquiring the citizenship of an EU Member State, where they lived, was 706.4 thousand in 2019, corresponding to a 5 % increase with respect to 2018. Germany had the highest number of persons acquiring citizenship in 2019, at 132.0 thousand (or 19 % of the EU total). The next highest levels of acquisition of citizenship were in Italy (127.0 thousand), France (109.8 thousand), Spain (99.0 thousand) and Sweden (64.2 thousand).

Figure 9: Number of persons having acquired the citizenship of an EU Member State, EU, 2009–2019

(1 000)

Source: Eurostat (migr_acq)

In absolute terms, the highest increases compared with 2018 were observed in Germany, as 15 200 more residents were granted German citizenship, followed by Italy (+14 500), Spain (+8 200), the Netherlands (+6 300) and Belgium (+4 400). By contrast, the largest decreases in absolute terms were observed in Greece (11 500 less persons were granted Greek citizenship compared with 2018), followed by Ireland (-2 400) and Luxembourg (-1 300).

Table 7: Acquisitions of citizenship by group of previous citizenship, 2019

Source: Eurostat (migr_acq)

Some 598.5 thousand citizens of non-member countries residing in an EU Member State acquired EU citizenship in 2019, corresponding to a 6 % decrease with respect to 2018. As such, citizens of non-member countries accounted for 85 % of all persons who acquired citizenship of an EU Member State in 2019. These new EU citizens were mainly from Africa (26 % of the total number of citizenships acquired), Europe outside of the EU (26 %), Asia (18 %) as well as North and South America (15 %).

Citizens of EU Member States who acquired citizenship of another EU Member State amounted to 91.1 thousand persons, thus accounting for 13 % of the total.

In Luxembourg and Hungary the majority of new citizenships granted were to citizens of another EU Member State. In the case of Luxembourg, Portuguese citizens accounted for the largest share, followed by French, Belgian and Italian citizens, while in the case of Hungary EU nationals acquiring citizenship were almost exclusively Romanians.

In 2019, Moroccans were the largest group among new EU-citizens (66 800 persons, of whom 84% acquired citizenship of Spain, Italy or France), ahead of Albanians (41 700, 62% acquired citizenship of Italy), Britons (29 800, 75% acquired citizenship of Germany, Sweden or France), Syrians (29 100, 69% acquired citizenship of Sweden), Turks (28 600, 57% acquired German citizenship), Romanians (26 600, 60% acquired citizenship of Italy or Germany), Brazilians (23 500, 73% acquired citizenship of Italy or Portugal), Ukrainians (18 100, 59% acquired citizenship of Germany, Poland or Italy), Algerians (18 000, 82% acquired French citizenship) and Russians (16 400, 31% acquired German citizenship).

Grants of citizenship increased for two of the highest five citizenships of origin, Britons by 84 % (from 16 200 in 2018 to 29 800 in 2019) and Syrians by 82 % (from 16 000 in 2018 to 29 100 in 2019). However, grants of citizenship decreased for Albanians by 12 % (from 47 400 in 2018 to 41 700 in 2019), and remained stable for Turks (28 600 in 2019) and for Moroccans (66 800 in 2019). Compared to 2018, Moroccans and Albanians remained the main recipients, while Britons moved from seventh to third place.

Highest naturalisation rates in Sweden and Romania

One commonly used indicator is the 'naturalisation rate', defined here as the ratio between the total number of citizenships granted and the stock of non-national residents at the beginning of the same year. The EU Member State with the highest naturalisation rate in 2019 was Sweden (7.0 acquisitions per 100 non-national residents), followed Romania (4.7) and Portugal (4.4), followed by Finland (3.8), the Netherlands (3.2) and Belgium (2.9). At the opposite end of the scale, naturalisation rates below 1 citizenship acquisition per 100 resident foreigners were recorded in Lithuania (0.2), Denmark (0.3), Estonia (0.4), Czechia (0.5), Latvia (0.6), Austria (0.7), Bulgaria and Slovakia (0.8 each) as well as Malta and Ireland (0.9 each).

Figure 10: Naturalisation rate, 2019

(acquisition of citizenship per 100 resident foreigners)

Source: Eurostat (migr_acq)and (migr_pop1ctz)

Data sources

Emigration is particularly difficult to measure. It is harder to keep track of people leaving a country than those arriving, because for a migrant it is very often much more important to interact about his/her migration with the authorities of the receiving country than with those of the country he/she is leaving. An analysis comparing 2019 immigration and emigration data from the EU Member States (mirror statistics) confirmed that this was true in many countries — as a result, this article focuses on immigration data.

Eurostat produces statistics on a range of issues related to international migration flows, non-national population stocks and the acquisition of citizenship. Data are collected on an annual basis and are supplied to Eurostat by the national statistical authorities of the EU Member States and EFTA countries.

Legal Sources

Since 2008 the collection of migration and international protection data has been based on Regulation 862/2007 and the analysis and composition of the EU, EFTA and candidate countries groups as of 1 January of the reference year are given in the implementing Regulation 351/2010. This defines a core set of statistics on international migration flows, population stocks of foreigners, the acquisition of citizenship, residence permits, asylum and measures against illegal entry and stay. Although EU Member States may continue to use any appropriate data sources according to national availability and practice, the statistics collected under the Regulation must be based on common definitions and concepts. Most EU Member States base their statistics on administrative data sources such as population registers, registers of foreigners, registers of residence or work permits, health insurance registers and tax registers. Some countries use mirror statistics, sample surveys or estimation methods to produce migration statistics. The implementation of the Regulation is expected to result in increased availability and comparability of migration statistics.

As stated in Article 2.1(a), (b), (c) of Regulation 862/2007, immigrants who have been residing (or who are expected to reside) in the territory of an EU Member State for a period of at least 12 months are enumerated, as are emigrants living abroad for more than 12 months. Therefore, data collected by Eurostat concern migration for a period of 12 months or longer: migrants therefore include people who have migrated for a period of one year or more as well as persons who have migrated on a permanent basis. Data on acquisitions of citizenship are collected by Eurostat under the provisions of Article 3.1.(d) of Regulation 862/2007, which states that: 'Member States shall supply to the Commission (Eurostat) statistics on the numbers of (…) persons having their usual residence in the territory of the Member State and having acquired during the reference year the citizenship of the Member State (…) disaggregated by (…) the former citizenship of the persons concerned and by whether the person was formerly stateless'.

Definitions:

The EU aggregates on Acquisitions of citizenship data for 2012, 2011 and 2010 include Romanian data for 2009.

Acquisition of citizenship data are rounded to the nearest multiple of 5 for Germany on provisional basis for 2018 and 2019.

Acquisition of citizenship data by individual former citizenship are not available for Romania for 2017, 2018 and 2019.

The EU aggregates on acquisitions of citizenship data by single former citizenship are computed without Romania data for 2017, 2018 and 2019.

The EU aggregates on immigration by country of previous residence and emigration by country of next residence data for 2013-2019 includes the United Kingdom in the composition of the EU because data related to the new composition of the EU is not available for Cyprus. The same applies to Malta for 2019.

The EU aggregates on population by citizenship data as of 1 January 2020 includes the United Kingdom in the composition of the EU because data related to the new composition of the EU is not available for Cyprus and Malta.

Age:

Concerning the definitions of age for migration flows, please note that 2019 data concern the respondent's age reached or age at the end of the reference year for all EU Member States with the exception of Ireland, Greece, Austria, Malta, Romania and Slovenia. In these countries data concern the respondent's age completed or on their last birthday. Concerning the definitions of age for acquisitions of citizenship, please note that 2019 data concern the respondent's age reached or at the end of the reference year for all EU Member States with the exception of Germany, Greece, Ireland, Austria, Lithuania, Malta, Romania and Slovenia. In these countries data concern the respondent's age completed or on their last birthday.

Member States and EFTA countries by inclusion/exclusion of asylum seekers and refugees in the data on population reported to Eurostat in the framework of the Unified Demographic data collection Reference Year 2019

| Population as of 01.01.2020 | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Asylum seekers usual residents for at least 12 months | Belgium, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, United Kingdom, Norway, Switzerland | Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Liechtenstein |

| Refugees usual residents for at least 12 months | Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland |

Note: Norway (Asylum seekers and refugees without residence permit are not included)

Member States and EFTA countries by inclusion/exclusion of asylum seekers and refugees in the data on migration reported to Eurostat in the framework of the Unified Demographic data collection Reference Year 2019

| Migration for 2019 | Included | Excluded |

|---|---|---|

| Asylum seekers usual residents for at least 12 months | Belgium, Germany, Estonia, Greece, Spain, France, Italy, Cyprus, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Austria, Portugal, Switzerland, Norway | Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Ireland, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Malta, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Liechtenstein |

| Refugees usual residents for at least 12 months | Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Ireland, Greece, Spain, France, Croatia, Italy, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary, Malta, the Netherlands, Austria, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland, Sweden, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Switzerland |

Note: Norway (Asylum seekers and refugees without residence permit are not included); Ireland (Refugees who do not live in a private household are not included)

Refugee: The term does not solely refer to persons granted refugee status (as defined in Art.2(e) of Directive 2011/95/EC within the meaning of Art.1 of the Geneva Convention relating to the Status of Refugees of 28 July 1951, as amended by the New York Protocol of 31 January 1967) but also to persons granted subsidiary protection (as defined in Art.2(g) of Directive 2011/95/EC) and persons covered by a decision granting authorisation to stay for humanitarian reasons under national law concerning international protection.

Asylum seeker: First-time asylum applications are country-specific and imply no time limit. Therefore, an asylum seeker can apply for first time in a given country and afterwards again as first-time applicant in any other country. If an asylum seeker lodges once more an application in the same country after any period of time, (s)he is not considered again a first-time applicant.

Naturalisation rate: The term 'naturalisation rate' should be used with caution because the numerator includes all modes of acquisitions and not just naturalisations of eligible residing foreigners and the denominator includes all foreigners, rather than foreigners who are eligible for naturalisation.

Context

Citizens of EU Member States have freedom to travel and freedom of movement within the EU's internal borders. Migration policies within the EU in relation to citizens of non-member countries are increasingly concerned with attracting a particular migrant profile, often in an attempt to alleviate specific skills shortages. Selection can be carried out on the basis of language proficiency, work experience, education and age. Alternatively, employers can make the selection so that migrants already have a job upon their arrival.

Besides policies to encourage labour recruitment, immigration policy is often focused on two areas: preventing unauthorised migration and the illegal employment of migrants who are not permitted to work, as well as promoting the integration of immigrants into society. Significant resources have been mobilised to fight people smuggling and trafficking networks in the EU.

Within the European Commission, the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs is responsible for the European migration policy. In 2005, the European Commission relaunched the debate on the need for a common set of rules for the admission of economic migrants with a Green paper on an EU approach to managing economic migration (COM(2004) 811 final) which led to the adoption of a policy plan on legal migration (COM(2005) 669 final) at the end of 2005. In July 2006, the European Commission adopted a Communication on policy priorities in the fight against illegal immigration of third-country nationals (COM(2006) 402 final), which aims to strike a balance between security and an individuals' basic rights during all stages of the illegal immigration process. In September 2007, the European Commission presented its third annual report on migration and integration (COM(2007) 512 final). A European Commission Communication adopted in October 2008 emphasised the importance of strengthening the global approach to migration: increasing coordination, coherence and synergies (COM(2008) 611 final) as an aspect of external and development policy. The Stockholm programme, adopted by EU heads of state and government in December 2009, set a framework and series of principles for the ongoing development of European policies on justice and home affairs for the period 2010 to 2014; migration-related issues are a central part of this programme. In order to bring about the changes agreed upon, the European Commission enacted an action plan implementing the Stockholm programme – delivering an area of freedom, security and justice for Europe's citizens (COM(2010) 171 final) in 2010.

In May 2013, the European Commission published the 'EU Citizenship Report 2013' (COM(2013) 269 final). The report noted that EU citizenship brings new rights and opportunities. Moving and living freely within the EU is the right most closely associated with EU citizenship. Given modern technology and the fact that it is now easier to travel, freedom of movement allows Europeans to expand their horizons beyond national borders, to leave their country for shorter or longer periods, to come and go between EU countries to work, study and train, to travel for business or for leisure, or to shop across borders. Free movement potentially increases social and cultural interactions within the EU and closer bonds between EU citizens. In addition, it may generate mutual economic benefits for businesses and consumers, including those who remain at home, as internal obstacles are steadily removed.

The European Commission presented a European Agenda on Migration (COM(2015) 240 final) outlining immediate measures to be taken in order to respond to the crisis situation in the Mediterranean as well as steps to be taken in the coming years to better manage migration in all its aspects on 13 May 2015.

The European migration network published annual report on immigration and asylum(2016) in April 2017. It provides an overview of the main legal and policy developments taking place across the EU as a whole and within participating countries. It is a comprehensive document and covers all aspects of migration and asylum policy by the Directorate-General for Migration and Home Affairs and EU agencies.

On 15th of November 2017, the updated European Agenda on Migration focused on the refugee crisis, a common visa policy, and Schengen. Matters included resettlements and relocations, financial support to Greece and Italy, and facilities for refugees. Objectives included enabling refugees to reach Europe through legal and safe pathways, ensuring that relocation responsibility is shared fairly between Member States, integrating migrants at local and regional levels.

On the 4th of December 2018, the Commission published a progress reporton the implementation of the European Agenda on Migration, examining progress made and shortcomings in the implementation of the European Agenda on Migration. Focusing on how climate change, demography and economic factors create new reasons pushing people to move, it confirmed that the drivers behind migratory pressure on Europe were structural, thus making it all the more essential to deal with the matter efficiently and uniformly.

On the 16th of October 2019, the Commission published a progress reporton the implementation of the European Agenda on Migration, focusing on key steps required on the Mediterranean routes in particular, as well as actions to consolidate the EU's toolbox on migration, borders and asylum.

On 23 September 2020, the Commission presented a New Pact on Migration and Asylum, setting out a fairer, more European approach to managing migration and asylum. It aims to put in place a comprehensive and sustainable policy, providing a humane and effective long-term response to the current challenges of irregular migration, developing legal migration pathways, better integrating refugees and other newcomers, and deepening migration partnerships with countries of origin and transit for mutual benefit.

Some of the most important legal texts adopted in the area of immigration include:

- Article 20 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union Union law on EU citizens;

- Article 21 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union on EU citizens;

- Article 79 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union on border checks, asylum and immigration for third country nationals;

- Directive 2003/09/EC on reception conditions for asylum seekers;

- Directive 2003/86/EC on the right to family reunification;

- Directive 2003/109/EC on a long-term resident status for non-member nationals;

- Directive 2003/110/EC on assistance in cases of transit for the purposes of removal by air;

- Directive 2004/38/EC on the right of citizens of the Union and their family members to move and reside freely within the territory of the Member States;

- Directive 2004/81/EC on victims of trafficking;

- Directive 2004/82/EC on the obligation of carriers to communicate passenger data;

- Directive 2004/83/EC on qualification;

- Directive 2004/114/EC on the admission of students;

- Directive 2005/71/EC for the facilitation of the admission of researchers into the EU;

- Directive 2008/115/EC for returning illegally staying third-country nationals;

- Directive 2009/50/EC concerning the admission of highly skilled migrants.

- Directive 2009/52/EC concerning employer sanctions;

- Directive 2011/95/EC on standards for the qualification of third-country nationals or stateless persons as beneficiaries of international protection, for a uniform status of refugees eligible for subsidiary protection, and for the content for the protection granted;

- Directive 2011/98/EU on single application procedure for a single permit for third-country nationals to reside and work in the territory of a Member State and on a common set of rights for third-country workers legally residing in a Member State;

- Directive 2013/32/EU on common procedures for granting and withdrawing international protection;

- Directive 2013/33/EU on standards for the reception of applicants for international protection;

- Directive 2014/36/EU on seasonal workers;

- Directive 2014/54/EU on freedom of movement of workers;

- Directive 2014/66/EU on intra-corporate transferees;

- Directive 2014/67/EU on posted workers;

- Directive 2016/801/EU on students and researchers;

Legal documents - New pact on Migration and Asylum

Press material - New pact on Migration and Asylum

How Many Immigrants Came to the Us in 2017

Source: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Migration_and_migrant_population_statistics